The Universal Spiritual Path of Peace and Love

- stephenwebster21

- Sep 13, 2025

- 11 min read

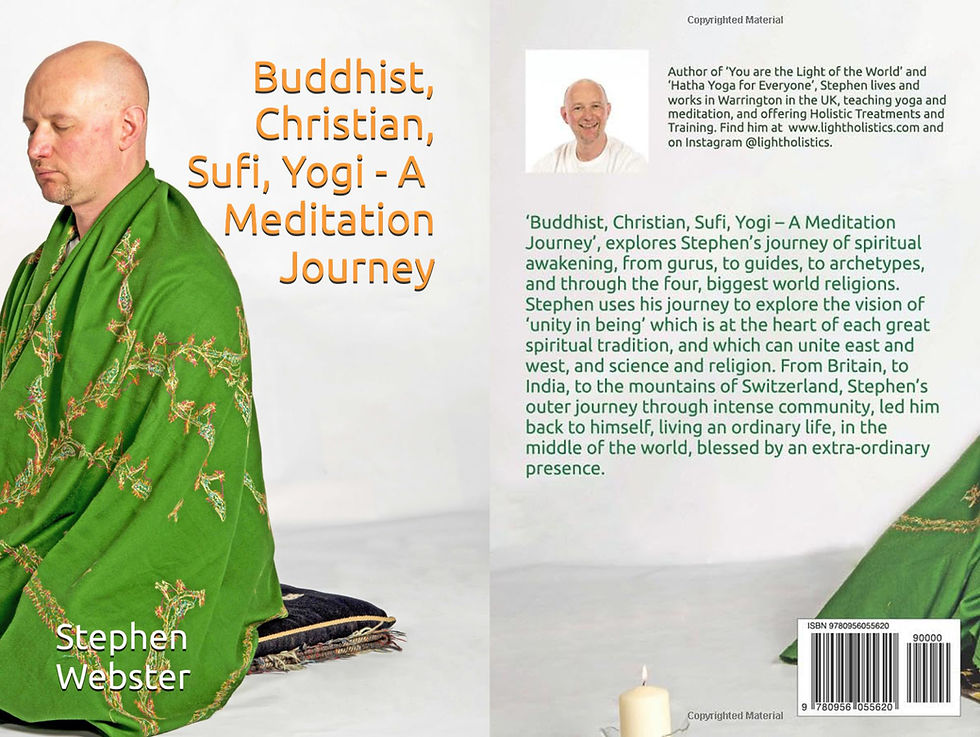

Here are the next 6 paragraphs from the opening Chapter of my latest book, ‘Buddhist, Christian, Sufi, Yogi – A Meditation Journey’, in which I entwine my own meditation journey with an exploration of the universal spiritual path of peace and love. Enjoy!

A Universal Path

My spiritual journey has led me to study and practise meditation in the four biggest spiritual traditions—Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam through Sufism. Throughout, I have practised Hatha Yoga, which uses a methodical, scientific sounding language to explain the steps and stages of the meditation process. I have travelled through the guru system, served the archetype on the altar, and practised the presence of the ‘all and everywhere’ in the ‘here and now’. I have found that there is generally a universal process, common to all spiritual paths. This is not a surprise because all spiritual traditions are seeking the same thing—unity in being. Each one starts from a different time, a different place, a different culture, and a different imbalance, and then moves towards the ultimate human experience of mystical union. Starting at different points on the mountain, each ends up with the same tool bag of techniques, by the time they have navigated their way to the top. After all, we are all navigating the same human condition. We can summarise this universal process with these eight simple steps. To meditate you need to choose your seat carefully, assume your posture, attune to your heart, breathe out completely and breathe in deeply, focus and stabilise your mind, become absorbed in the joy of being, rediscover your best self and live out your most beautiful life. This is the universal, and not complicated path of meditation, around which I have structured this book.

A Great Conversation

I once had a wonderful conversation with a young couple on a plane coming back from a break in Kefalonia. 'I will remember this conversation for the rest of my life', the young woman said, as we said our goodbyes. Somehow, we had got onto the meaning of life. My new friend went to a Catholic school. She was well on board with the whole faith thing at primary school, until she got to secondary school. Nothing taught at secondary school connected to the faith stories she was told at primary school. And nothing was done to explore the difference. She was simply meant to stick blindly to one-dimensional assertions, that she had pictured in a childish cartoon way, which didn’t relate in any way to the multi-dimensional universe she was learning about at secondary school. There was no old white man on a cloud with a beard, so she lost her faith. 'Of course, I said, that was never meant to be the meaning of the word 'God'. You were meant to get an upgrade. That’s what the confirmation process was supposed to be about—an adult exploration of faith with discussions, debates, doubts, and the incorporation of critical, rational thinking—a faculty which awakens so much in adolescence. For example, St Augustine, I explained, experienced God before he became a Christian. You can read this in his autobiography. He experienced what he called the ‘uncreated light’, and he experienced this in meditation. It wasn’t a man on a cloud.' 'Oh, said my friend, I hadn’t heard of that'. 'Let's talk about the virgin birth', I said, moving onto dangerous, but interesting territory. The young woman's boyfriend, who had had no faith upbringing, suddenly piped up, greatly animated, ‘Well of course, the whole universe is a virgin birth. Everything came out of nothing’. There was nothing inspiring or intelligent that I could add. 'That’s a really deep point you’ve just made there', was all I could say. 'Let's look at it like this, I went on, do you think life has a purpose. Do you feel that the universe, in some sense, has a heart?' 'Oh, I do think that', my friend said. 'Yes, there is a meaning to everything'. 'Well, that’s what believing in God means to me, I said, and I’m a practising Catholic. I definitely agree there is no white man, with a beard, on a cloud, though perhaps the being behind the whole universe is well capable of appearing to you like that if it helps!'

The Miracle of Life

There is an astonishing miracle at the heart of our existence that no number of clever theories can ever explain away. Once we were not, and now we are. You didn't create yourself and I didn't create myself. In the final analysis, the more we learn, the further the horizon recedes, the more we know, the more we know we don't know. Against the vastness of eternity, we are clutching at straws. Our life is a mystery, wrapped in an enigma, as the phrase goes. Out of nothing, 'I am', and this essential mystery and miracle, is our ultimate birthday present, for which we can be eternally grateful. In the end, I have nothing to assert, only a responsibility to live up to this moment in the spotlight, when you and I are aware that we exist, and we have the opportunity to do something about it.

Glasgow and St. Mungo—Signs, Symbols, and Stories

I was born in Glasgow, where I lived until my parents moved to Canterbury, when I was six months old. Glasgow's patron saint, first bishop, and possible effective founder, was St. Kentigern, popularly known as St. Mungo. As far as we know, St Mungo lived between AD 518 and AD 614, at the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon age, when Rome and many Romans had retreated, and Celts, Picts, Angles, Saxons, and others, fought over Britain. This is the time most often associated with the King Arthur legends. A famous verse from the life of St. Mungo relates to a bird, a tree, a bell, and a fish, telling the story of the four miracles of St. Mungo. When I read the story on a return visit to Glasgow, the miracle of the fish moved me the most. According to surviving stories, St. Mungo's mother, when pregnant with St. Mungo, was cast out on a boat to die in the sea, by her father who disapproved of her husband. This was a grim form of punishment at that time. Instead of drowning, she landed on Culross, where Mungo was born, and raised by Saint Serf, who was working with the Picts in that area. The story of the fish occurs much later, when Mungo is Bishop under the patronage of King Riderch. The king suspects his queen of infidelity and to frame her, on threat of execution, throws her wedding ring into the river, and then demands his queen to produce the ring, which he claims she has given to her lover. Queen Langaoreth turns to Mungo in desperation and Mungo prays and tells a messenger to catch a fish in the river, which it turns out, had swallowed the ring, allowing the queen to clear her name. What is so perfect about the story is you can sense Mungo's compassion for the queen, who like his own mother, was being treated cruelly by men. St. Mungo's tomb is in the crypt of Glasgow Cathedral, which is owned by the Church of Scotland. On the occasion of my visit, a note was attached to the story of St. Mungo, explaining that the miracles are made up stories. This is in keeping with the Protestant tradition, which likes to keep a distance from saints and miracles, even though ironically, the church is the custodian of the tomb of a saint.

It is a common practice of most historians to discount these miracle stories of the saints, on the basis that first, everybody knows miracles aren't real, second, the story is too perfect to be true, and third, similar stories are told about other people exploring similar themes. Of course, we don't know that they are true, and we do know that people do make up stories, but we don't know that they are not true either, unless we are working on the basis that due to our own belief system, they couldn't be true. My own experience of life is that the whole thing, from start to finish, is a miracle. And what is more, the stories that unfold every day, in front of our eyes, are truly remarkable, and in their own way utterly perfect. I love to watch the Olympics. They are full of incredible stories of individuals who have invested their life force in a passion, which suddenly comes true in a remarkable way. And yet when incredible stories are told about people from ancient times, who clearly were outstanding, just by the evidence of their achievements, the stories are instantly discounted. Perhaps, we could at least let the stories be, and let them breathe, whilst acknowledging that they are rooted in oral tradition rather than material evidence.

The deeper I penetrate in meditation and contemplation, the more life around me seems to be like a story book, full of signs, symbols, and stories, unravelling the wisdom of a supreme being, into which I am being drawn. Whilst I can choose to take one path or another in my life story, either way a universal theme will develop along archetypal lines, riding the waves that emerge from the sea of our universal being. Again, and again, my story, like everyone's story, has unravelled in a particularly unique way, that creatively explores common themes. The miracles of the saints often have unusually specific and unique details, which open up archetypal realities in a personal and heart-warming way. A story lasts centuries because it touches something universal in the human heart, and you either believe that is because the being behind creation reveals him, her, and itself, that way, or you believe there are just some really good story tellers out there, who find ways to hoodwink whole communities for centuries. In the end we are inclined to believe what relates to the way we experience and live life, and we are inclined to dismiss what challenges our way of being and life.

The Spread of the Mystical Vision Around the Globe

I have always intuitively believed in the mystical vision of life. This is the story of how it became real to me, and to many other people in our wonderful human family. We are reaching a moment, as a species, when we’ve either got to embrace each other, or by clinging to our perceived separateness, go down in flames, or water, or both. As the Spiderman saying goes, ‘With great power comes great responsibility’, and as a community we continue to grow in power. At the heart of all the great faiths is a shared vision of unity in being. That is the vision that is going to count, if we are going to make it through the next phase of our evolution, and the evolution of our beautiful planet.

According to the Pew Research Centre’s 2012 estimate, only 16% of the world's population were agnostic, atheist, or self-identified as secular. The rest identified with one of the world's religions. These are much higher numbers than today’s popular discourse implies, where the impression is often created that science has replaced religion. Of those who identified with a faith, the big four religionswere Christianity—32%, Islam—23%, Hinduism—15%, and Buddhism—7%. Seventy-seven percent of the world's population identified with these big four religions. Hinduism is the oldest religion of the big four, estimated to be at least 4000 years old by many researchers, although it could easily have roots that go back much further. Unlike the later three traditions, there is no one belief system attached to Hinduism—rather, a series of traditions and practices that are associated with a range of beliefs. There is, however, one core understanding that underlies the 'eternal dharma', as the religion calls itself—the belief in one universal being or God, and the understanding that God is both beyond all names and forms, and within all names and forms, and can therefore be approached by many different names and forms. Many paths up the mountain, but one summit. This is a great gift from India to the world, that is still widely misunderstood, both by believers who think that the unlimited God can be limited to one name and form, and by atheists who promote the idea that believers follow millions of different Gods, and that they can’t all be right, and so the whole thing is irrational.

Hinduism affirmed the mystical unity of the divine being, which makes all beings one. The other three great religions emerged within a very small span of human history. Buddhism, as a simplification, a reform, and, you could argue, a rationalisation of Hinduism, around 6 BC. Christianity, which emerged, according to the Christian tradition, as the fulfilment of the Jewish revelation around AD 33, and Islam, which emerged, according to Islamic tradition, as the final fruit of the Prophetic line—the 'Seal of the Prophets', around AD 610. When you consider that Islam has so far proved to be the last great religion, just going by the numbers, it does indeed ring true that it was the end of a particular line of revelation of the One God. That doesn’t mean that new revelations haven’t emerged since. They haven’t stopped emerging. But the one God, or Being, had already covered the globe, and each religion eventually emerged with its zone of influence in the world, which remains fairly stable. India is predominantly Hindu. The Far East is predominantly Buddhist. Europe, the Americas, and Southern Africa, are predominantly Christian, and the Middle East and North Africa are mostly Muslim. The next biggest group of belief, covering 6% of the world's population, according to the 2012 survey, are what are sometimes categorised as the folk religions, that originally existed in many of these areas. This includes Aboriginal, Indigenous, First People's, and tribal cultures, which often link to the Shamanistic traditions of our hunter gatherer ancestors. These deserve a special mention, because in many ways these traditions live alongside, and are incorporated into, the big four religions. All the big four religions maintain older traditions, found in many of the ceremonies particular to different regions. When you go into detail, with genuine understanding, you will find that nearly all the Indigenous religions believe in one universal spirit, with many forms, as reflected in the multiplicity of nature, often evoking the archetypes of Mother Earth and Father Sky.

Understanding a Tradition from The Inside

My rule of thumb when understanding a religion has been to talk to people, even better to practice with people, actually living the religion, rather than rely on what a teacher may have told me in school, based on an outdated, possibly prejudiced, and usually oversimplified textbook. Many Christian theologians and professors, when exploring Buddhism, from the outside, assert that Buddhism ultimately believes in a 'nothingness', which they contrast with the Christian heavenly vision of a diverse unity. In fact, when you study with Buddhist masters, you realise that Buddha did not believe in nothingness. He taught ‘not nothing and not something’. All ideas about reality are 'uncertain', he declared. The ultimate is an experience and an awakening, beyond concepts—that was his point. Thomas Aquinas, writer of huge books (his 'Summa Theologiae' is 1.8 million words!) and a Doctor of the Church, had a mystical encounter with Christ at the end of his great career as a medieval theologian. In a similar vein to the Buddha, he declared that all he had written was ‘like straw’, compared to his experience, and he ceased writing, shortly before passing away. At the same time, eastern teachers sometimes appear to misunderstand Christianity. The cross means crossing out the ego they explain. From a Christian perspective that is certainly part of what the cross is about, but it is more deeply about the attempt to cross out an enlightened, awakened, pure, or divine being, and the transforming resurrection of creation that occurs as a result. At an even deeper level, what happened to Christ is a reflection of the sacrifice of the One to become the many, and how that act of creation, inevitably involving suffering, nevertheless produces a love that makes the whole thing worthwhile. We all contain that eternal spark, and so we all experience that crucifixion of innocence that living entails, but we also all participate in the creation of love that the challenging process facilitates. There is a meaning and purpose to the actual creation of life, which goes beyond stepping off the wheel and going back home. We are going somewhere in our return; we are creating something in our spiralling growth. God is both dynamic and static, both going somewhere and already arrived. Our essential being is ultimately about peace, and where we are going is ultimately about love.

If you're gripped purchase on amazon via author links below!

Comments